Welcome

Welcome

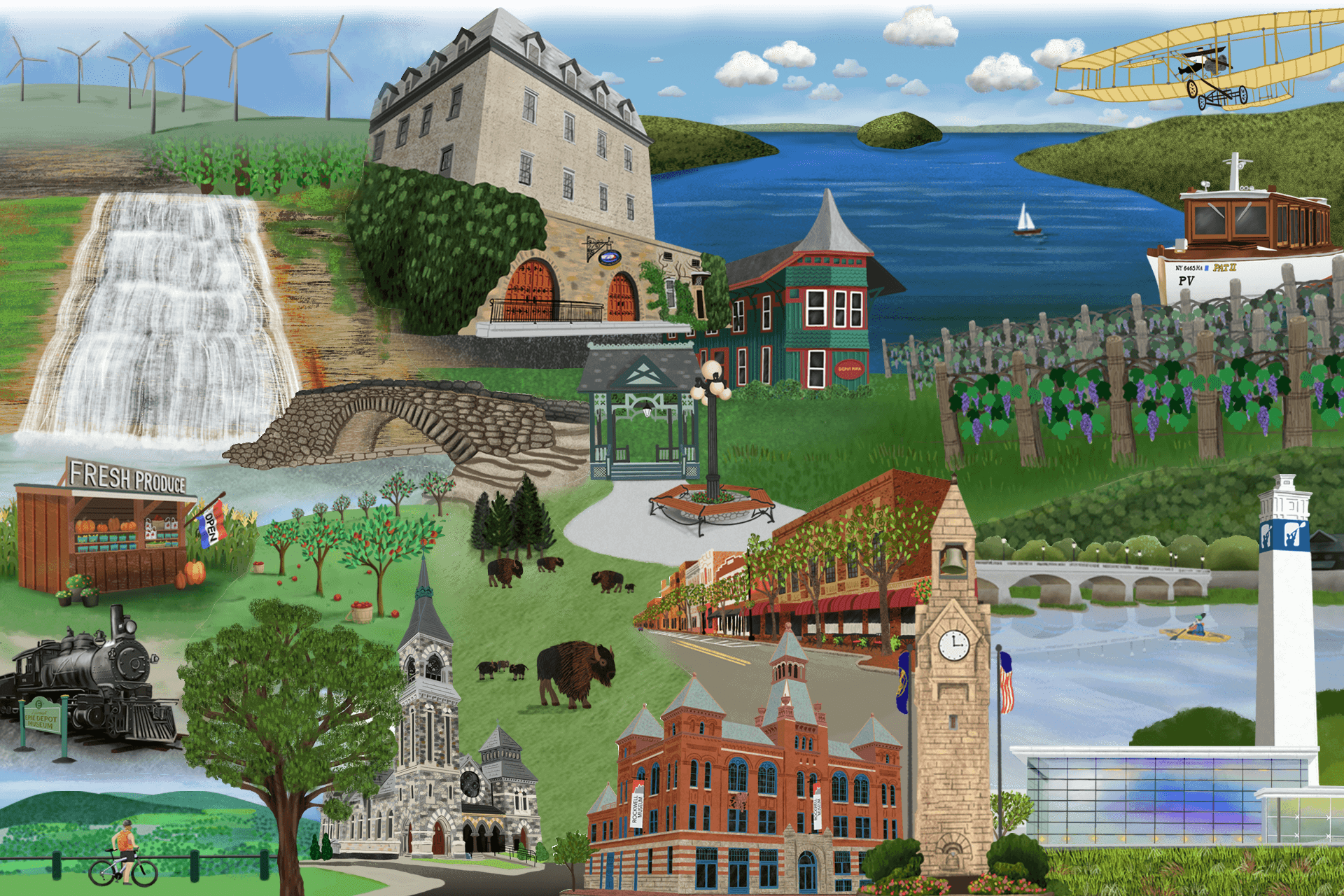

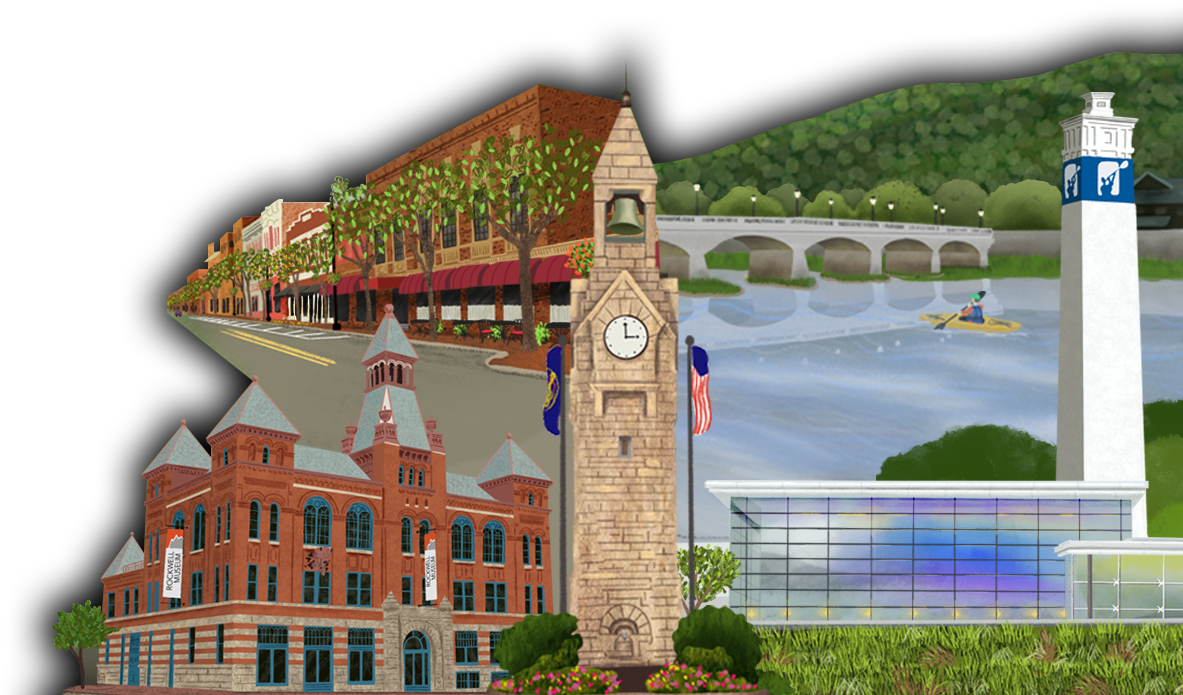

Embark on your Finger Lakes journey and immerse yourself in breathtaking landscapes, enchanting waterfalls, award-winning wineries, charming small towns, and the captivating artistry of hot glass – your ultimate vacation experience begins here!

Embark on your Finger Lakes journey and immerse yourself in breathtaking landscapes, enchanting waterfalls, award-winning wineries, charming small towns, and the captivating artistry of hot glass – your ultimate vacation experience begins here!

Experience Glass

Experience Glass

Spend some time in America’s Crystal City and you’ll discover just how remarkable something as ordinary as glass can truly be.

Discover just how remarkable something as ordinary as glass can truly be.

Explore

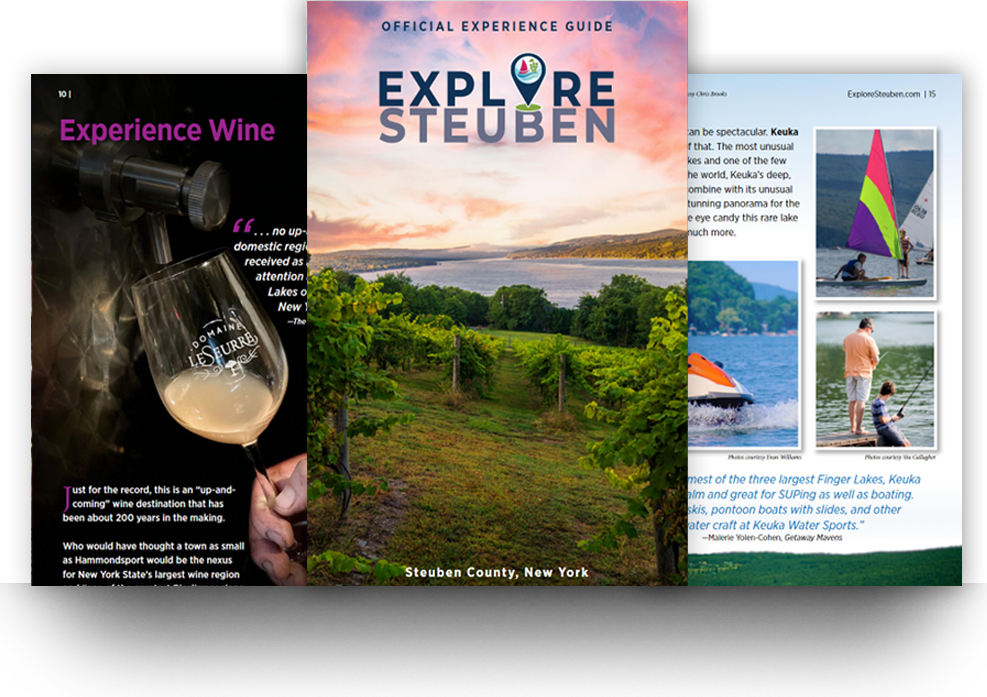

Experience Wine

Experience Wine

In some ways, New York State’s recent emergence on the international wine stage seems surprising. After all, most people only think of the Big Apple when they think of the Empire State. And that doesn’t typically elicit images of vineyards and wine barrels.

Learn about New York State’s recent emergence on the international wine stage.

Explore

Experience Keuka Lake

Experience Keuka Lake

The most unique and arguably the most stunning of all the Finger Lakes, Keuka (pronounced Q-KA) is the only Finger Lake not shaped like a finger as it is one of the few Y-shaped lakes in the world.

Explore Keuka Lake - one of the few Y-shaped lakes in the world.

Explore

Experience Outdoors

Experience Outdoors

We can’t take credit for all the remarkable scenery you’ll find here. We’ve just figured out the best ways to make the most of it. Paddle, hike, bike, camp. Prepare to be wowed!

We can’t take credit for all the remarkable scenery you’ll find here.

Explore

Bath

Corning

Hammondsport

Hornell

May 2024 May 2024

Full Details Courtesy: The Corning Museum of Glass Courtesy: The Corning Museum of GlassAugust 12th-18th, 2024 August 12th-18th, 2024

Steuben County Fair Courtesy: Explore Steuben Courtesy: Explore SteubenOctober 6, 2024 October 6, 2024

View Race Series Courtesy: Wineglass Marathon Courtesy: Wineglass Marathon